The New Wave (1979-1986)

Share

After the departure of Bangs, Uhelszki and Marsh, Susan Whitall keeps the punk rock flame burning bright.

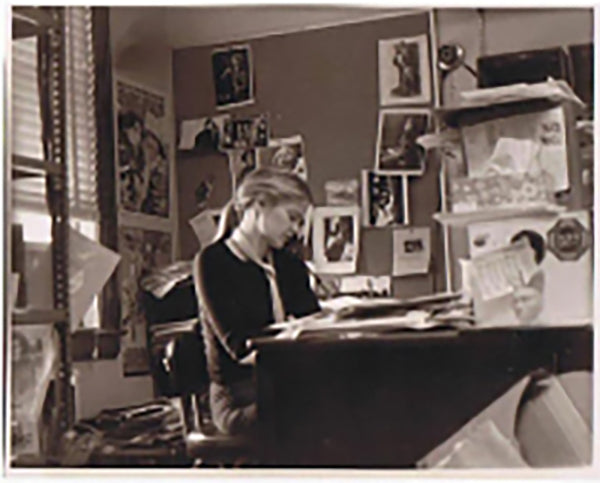

Of all the junk paper on my desk at CREEM, one of my favorites was a black and white cartoon scotch-taped to my desk lamp. It showed a ponytailed teenaged girl, pen in hand, with the title: “My Editor.”

That’s what I was to Robot A. Hull, who sent it to me, and a motley crew of Lost Boys (and Girls) to whom I was Wendy when I became editor after Lester Bangs, Jaan Uhelszki and Robert Duncan left in 1976.

Over time the legend has become Lester Bangs = CREEM, but when I started working in the dank old Birmingham office in 1975 there were many loud voices in the editorial department. It was actually the Managing Editor, or Editor (Lester was Senior Editor), who assigned the stories, argued with Barry Kramer over the cover image and paid the writers.

By late 1977, that was me.

Despite the patchouli-scented promises of the Sixties counterculture, sexism was still rampant at music magazines. But unlike Rolling Stone, CREEM had women as content editors. Still, when I asked for the title of Editor, a job I was already doing, Barry snarked: “You’re too young and too female.” Ah, but then he gave it to me...

Since 1975, I’d been trained in the John Morthland/Lester Bangs school of editing and proofreading—no, don’t laugh. Lester fly-specked every word on every page, in an editing process John had put in place. It was important to me that there was continued improvement in editorial consistency and polish, beyond the Cass hippie flophouse “we don’t need no masthead” days.

But I didn’t want the magazine to be too slick or commercial, either. I believed deeply that the essence of CREEM was rooted in Detroit and in being scrappy Midwestern outsiders. I had no intention of allowing our increasingly robust national distribution make us part of the boring mainstream. We liked it out beyond the sidewalks.

Our roots in the Michigan boondocks meant that we didn’t spurn such populist acts as Grand Funk Railroad, J. Geils Band or yes, Van Halen. (But not Journey. I drew the line at Journey. That would have to wait until after I left.).

But when I did assign a story on a mainstream band, it helped to have someone like Dave DiMartino cover it, who wouldn’t turn in a lazy or conventional music mag story. The opening line in his 1980 piece on Van Halen entitled “Remnants of the Flesh Hangover: If You Hate Van Halen, You’re Wrong” was: “One thing that’s always bothered me about myself: I enjoy offending people.”

It was also important that we kept our readers educated about punk and other tattier music genres. When new wave started to dominate, our cover images reflected that, with Blondie, Elvis Costello, the Police and the Clash.

Barry Kramer was all for covering punk and new wave, but on the cover, he preferred gazillion-selling artists such as Led Zeppelin. We argued. I told him this was the equivalent of writing about zero-selling acts such as the Stooges, back in the day, which was important for us, culturally. He admitted I was right, despite the slower sales figures for those acts.

At the same time, when we lacked a cover-worthy story one month, I had no problem writing a Led Zeppelin think piece, fueled by Tab and panic. Okay, here you go, Led Zep on the cover, it’ll sell gangbusters and we’ll be able to pay the printer’s bill for a few months.

The great intangible that set CREEM apart from our competitors was that it could be as entertaining as the music was. I had fun writing the Led Zeppelin “psycho-biograph” that paid the printer that month. After all, with rock musicians as outlandish, pompous and fascinating that they were, why should coverage of them be boring?

Even when we gave space to deep thinkers and more thoughtful writers, it was always with a CREEM-worthy backspin.

Nick Tosches, like most of our writers, always needed money. But the copy we got from him in return for his modest checks was never less than thrilling. On one occasion he sold us “Jerry Lee Lewis: God’s Garbage Man,” an excerpt from an upcoming book he was working on entitled Country: The Biggest Music in America. But forget paying the publisher, we made sure that the money went straight to Nick’s mailbox in Jersey City.

That piece led to the 1979 debut of Nick’s excellent “Unsung Heroes of Rock ‘n’ Roll” column, introducing CREEM readers to such foundational, pre-rock greats as Wynonie Harris, Louis Jordan and Roy Brown. His descriptions of the world of early and mid-’50s R&B had the colorful, teeth-rattling detail of noir fiction. It may have been a history lesson, but it still felt like CREEM and we were proud when the column evolved into a well-regarded book.

When it came to humor, I kept a permanent financial pipeline in place between Birmingham and Rick Johnson’s squat in Macomb, Illinois. His blunt, homespun humor flowered with such cultural think pieces such as “How to be a Rock Critic in One E-Z Lesson,” “Is Heavy Metal Dead?” (alas, no), guides to beer and guitar heroes, and our “Dubious Achievements.”

“I had no intention of allowing our increasingly robust national distribution make us part of the boring mainstream.”

It makes me smile to think of pony-tailed Rick-Robot A. Hull was another CREEM original. His “That’s Cool, That’s Trash: A History of the First Punk Era,” published in June 1979, was one of the first stories to illustrate the synergy between early garage rock and punk; and his monthly collaborations with cartoonist The Mad Peck added a unique extra dimension to our review section. Many of our stories came out of friendly arguments (real and fake) that spilled over into print. Take “Clash versus Led Zeppelin” by Janie Jones and Geddy Lee Roth. This December 1980 epic consisted of an argument between a Clash fan, Janie Jones (me) and a Led Zeppelin fan, Geddy Lee (Dave DiMartino). Both of us were fans of er, both bands. This was classic CREEM sport, the kind of thing we did while proofreading. It was a goof, but the story epitomized the deep breach in music that was widening with every day. (Geddy was so angry about the use of his name, that when John Kordosh was assigned a Rush story a year later, he wouldn’t talk to him. It only made John’s story “Rush: What’s the Hurry” all the better.) It’s somewhat of a myth that the magazine “went metal” in the later years. The CREEM Metal specials were created to please fans of that genre, starting in 1983. That allowed us to run the occasional mouthy piece on a hard rock act in the regular magazine, with the bulk of the headbanging content going to CREEM Metal—where the Triumvirate of Metallic Wisdom—aka Dave DiMartino (Martin Dio), Bill Holdship (Jesse Grace) and John Kordosh (Hal Jordan) skewered heavy rock pretensions in classic CREEM style.

When alternative music heated up, we gave career-making boosts to such acts as the Replacements (Bill Holdship had the franchise locked up) and Robyn Hitchcock, who made the cover of CREEM while he was still an indie artist. Many who have seen the recent CREEM documentary remark upon the darkness that seems to descend after Lester leaves and Barry Kramer’s life, and then, Connie’s, go into a downward spiral. But it wasn’t dark in our editorial offices. We had the best jobs in music journalism. We were going on the road with acts who often became friends and writing what we wanted, with little intervention. (How could I gripe about drinking Black Velvets in a limo with Rory Gallagher, or dancing at a press party with George Harrison). We wrote headlines and cutlines embedded with coded in-jokes referencing Elvis movies, Bad Axe, Green Acres, and other obsessions, often written in the voice of Mr. T. We were a suburban street gang with Blue Cross, free records and all the Maxwell House coffee we could drink.

Don’t tell anybody, but we might have done it for free. (Well, okay, we almost did.) Boy Howdy is dead… long live Boy Howdy!